Changes occur before gluten is introduced, first published results of the broad study of at-risk infants finds

By Amy Ratner, Medical and Science News Analyst

When scientists working on a study of children at-risk for celiac disease published the first results of their research recently, one audience was especially excited about the news.

That’s why the team from the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at Mass General Hospital for Children quickly set up a Zoom meeting so parents of children enrolled in the study could be among the first to learn what the investigators had found. These are, after all, the people who have been diligently collecting the children’s stool samples and sending them to the center for analysis.

Study results show that cesarean delivery, antibiotics at birth and formula feeding cause changes in the gut of infants at-risk for celiac disease that are linked to dysfunction of the immune system and to inflammatory conditions.

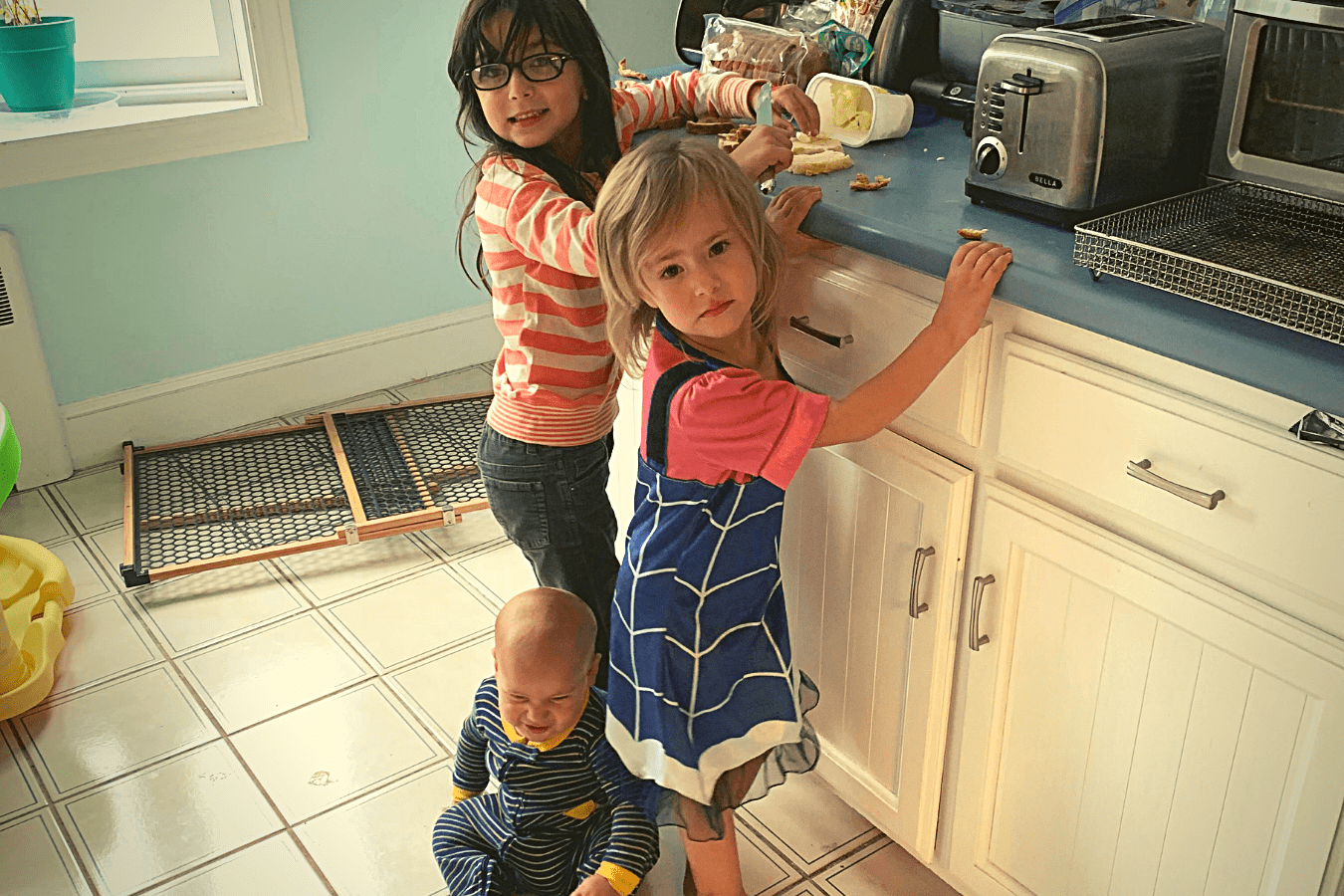

“I was super excited. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, we will finally get to see some results,” said Theresa Moutafis, who was pregnant with her daughter Grace, now 6, when she enrolled her. In fact, Grace was the first child signed up for the Celiac Disease Genomic Environmental Microbiome & Metabolic study, more often and affectionately referred to as the GEMM study. Moutafis, who has celiac disease, has also enrolled her two other children, Gabby, now 3, and A.J., now 8 months.

“I was super excited. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, we will finally get to see some results,” said Theresa Moutafis, who was pregnant with her daughter Grace, now 6, when she enrolled her. In fact, Grace was the first child signed up for the Celiac Disease Genomic Environmental Microbiome & Metabolic study, more often and affectionately referred to as the GEMM study. Moutafis, who has celiac disease, has also enrolled her two other children, Gabby, now 3, and A.J., now 8 months.

Scientists looked at stool samples of three-to-six month old GEMM babies who had not yet eaten any gluten to investigate the effects of genetic risk, how a baby was delivered, whether he or she was given antibiotics at birth and whether the baby was fed formula or breast milk.

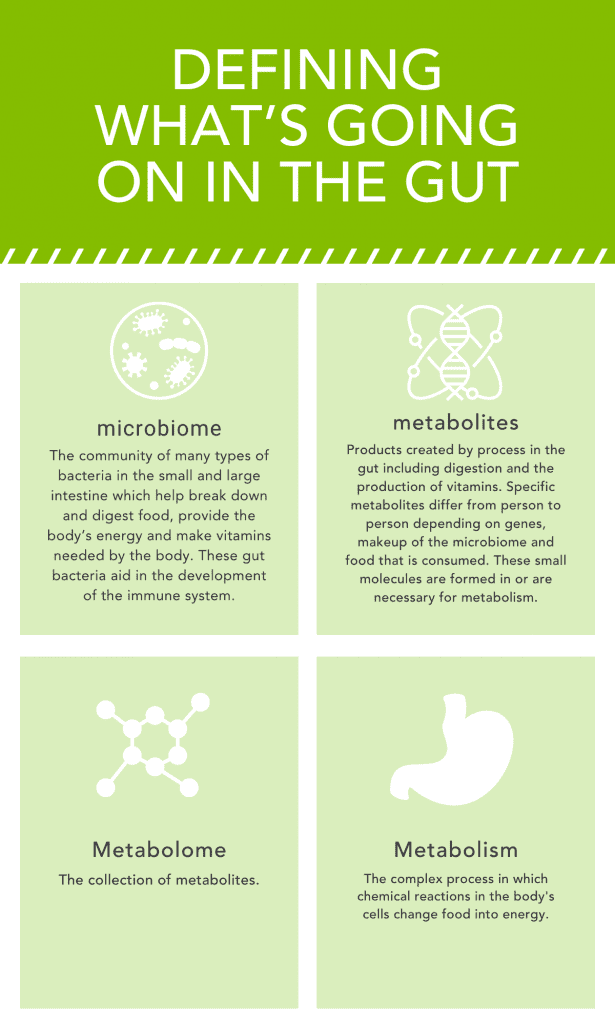

Stool samples provide information about the microbiome, the diverse community of bacteria that live in the gut and influence the development of the immune system. The microbiome is thought to play a role in the development of celiac disease.

“The important finding is that we can identify changes in the microbiome associated with underlying genetic and environmental factors in infants at risk of celiac disease even before gluten is ever introduced,” said Maureen Leonard, MD, lead study author and clinical director of the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment. “This suggests that environmental exposures in early life may alter the trajectory towards developing celiac disease in children at risk, though further study is needed.”

Babies who had been exposed to any of the three environmental factors had more negative intestinal characteristics, while those who were not exposed to any of the factors showed signs linked to beneficial immune system and anti-inflammatory effects.

It’s too early to link the study results to predictions about which at-risk babies will develop celiac disease, according to Leonard. But it’s a step toward understanding of how celiac disease develops and what might be done to prevent it, which is the overall goal of the GEMM study. Currently, a total of 478 babies in the United States and Italy are enrolled in the study, and researchers are aiming to get to a total of 500. Babies are considered at risk if they have a parent or sibling who has celiac disease.

“Since our study only followed the infants to six months, we can’t comment on whether the alterations we see contribute to disease onset,” Leonard explained. “We can just say that we see changes related to these environmental factors and underlying genetic type. We need to follow through the onset of celiac disease to see if the alterations actually play a role.” Leonard noted that the GEMM study is designed so researchers can work toward that goal.

“While our analysis suggests that the microbiome shifts that we observed during the first six months after birth increase the risk of developing autoimmune conditions including celiac disease,…it is unclear whether they indeed contribute to the future development of celiac disease,” the study says.

The research results, published in the journal Microbiome, are the first to come out of the larger GEMM study being done by investigators from Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at Mass General Hospital for Children and colleagues in Italy and Spain. Additional published research is expected in the future.

The study included 31 infants from whom stool samples had been collected since birth. Since none had consumed gluten over the first six months of life, scientists were able to look the impact of environmental factors on the microbiome independent of changes related to gluten exposure.

“None of these infants consumed solid foods before six months, which makes them ideal for studying the effect of genetic and environmental risk factors on the gut microbiota in the absence of gluten as a confounder,” the study says.

“We know gluten is the trigger for celiac disease. But are there other environmental factors even before the trigger of celiac disease is introduced,” Leonard explained, noting that the next question becomes do these factors predispose those who are at higher risk because of family history to get celiac disease. She noted that the study gives researchers a rare opportunity to look at changes in the microbiome before, during and after the development of celiac disease when many studies only compare those who already have a disease to those who don’t.

Twenty six of the infants had the genes associated with celiac disease. Nineteen had been exposed to at least one of the environmental risk factors, while seven were not exposed to any of the environmental risk factors.

Researchers looked at features of the microbiome, including microbial species, functional pathways and metabolites at birth, three and six months, to see how they are associated with genetic risk for developing celiac disease and with the three environmental factors under study. Cesarean section, antibiotic use and formula feeding were considered clinically relevant because c-section is often associated with antibiotic administration at birth and formula feeding due to a delay in breastmilk production, according to the study.

Study authors noted that other researchers are exploring alterations in the microbiome of infants at risk for a variety of autoimmune conditions, including type 1 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. But they point out that in celiac disease no systematic study of whether protective and detrimental genetic and environmental factors change the microbiome over the first months of life of infants at risk for celiac disease.

Researchers found that the microbiome of babies with genes for celiac disease who had been fed formula had increased amounts of bacterium linked to allergic diseases and diabetes. Some previous studies have found that breast feeding does not protect against development of celiac disease, but Leonard noted that other earlier research has shown that the gut microbiome is altered in terms of overall diversity and the amount of specific microbes depending on how an infant is fed. Likewise, the GEMM study found alterations associated with different feeding practices in children with a genetic risk for celiac disease.

Other “significant findings” are associations between cesarean delivery and patterns associated with impaired immune function and inflammatory conditions such as type 1 diabetes and ulcerative colitis. This suggests the patterns could also predispose infants to develop celiac disease, according to the study.

The kind of analysis done in the study looked not only at the kind of microbes in the microbiome, which is what many studies investigate, but also at the way in which they were functioning.

“We looked at not just who’s in there but who is contributing to changes in the underlying immune system,” Leonard said. “Who is contributing to changes in the pathogenesis of celiac disease.”

Small sample size was noted as a limitation of the study which the authors said could be addressed through ongoing enrollment of babies in GEMM to provide a larger sample size to validate the study results. Researchers hope to enroll a total of 500 babies. Future work should also consider more environmental factors and their impact on the development of celiac disease in at-risk infants, including viral infections, when gluten is introduced in the diet and how much of it is consumed. Household exposures are another area that needs to be further explored, including family size and exposure to pets, which have been reported to be associated with alterations in the microbiome.

Next steps in GEMM research will be to identify changes in the microbiome that occur before celiac disease develops in order to predict celiac disease and use that information to prevent it, according to Leonard.

“The current study lays the groundwork,” she said.

For the Moutafis family, the broader GEMM study has yielded important personal findings. Grace has developed celiac disease, which was diagnosed as part of the study. Meanwhile, it’s been determined that Gabby does not have the genes that are associated with celiac disease. A.J. will have the gene test as part of the study when he is about one-year-old.

But the family also has it eye on the bigger picture.

“There is so much more we can learn, so it’s very cool to be a GEMM,” Theresa Moutafis explains. “This study is so important and will have such wide reaching effects.” And Grace is old enough to understand that she and her siblings are part of the study to help. “We tell her it could help prevent or cure celiac disease,” her mother says. “She sometimes asks, ‘When are we going to get the gluten pill?’ We tell her, some day.”

Opt-in to stay up-to-date on the latest news.

Yes, I want to advance research No, I'd prefer not to