Researchers may eventually be able to use these clues to intervene to stop celiac disease

By Amy Ratner, Director Scientific Affairs

Intestinal changes that occur before the development of celiac disease in at-risk children have been identified in a new study.

These changes are giving researchers clues that may eventually enable them to intercept and possibly prevent celiac disease by adjusting the collection of micro-organisms in the gut, called the microbiome.

“With these findings we anticipate that we will be able to distinguish who will remain healthy and who will develop celiac disease months before the onset of the disease,” said Alessio Fasano, MD, director of the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at Mass General Hospital for Children and senior author of the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Results of this proof-of-concept study will need to be confirmed in larger studies, he added.

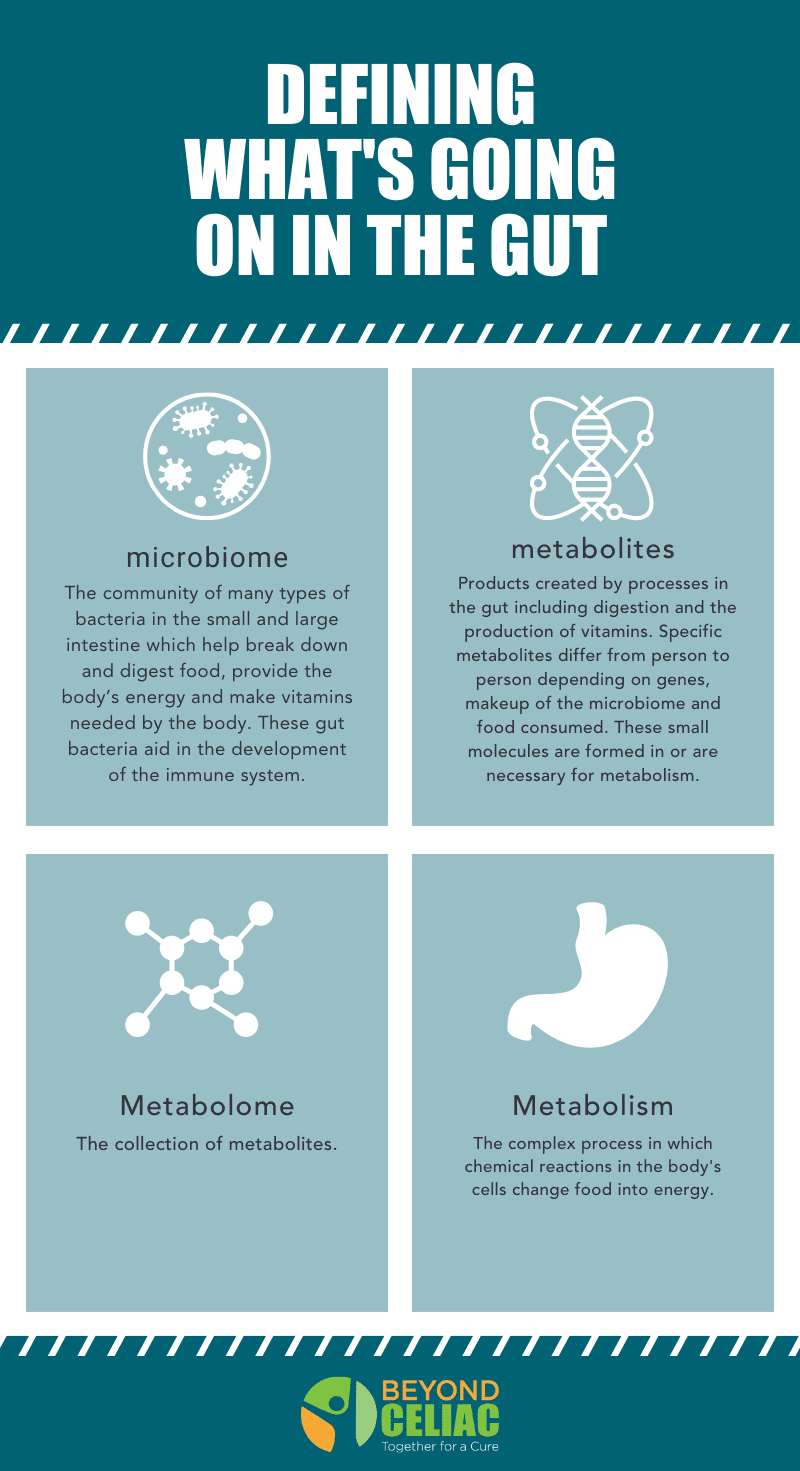

Substantial changes in the microbiome and the metabolome — the molecular components of cells and tissues — of children with a parent or sibling who has celiac disease were identified months before celiac disease developed, Fasano and colleagues found in the new study. The research is part of the larger Celiac Disease Genomic, Microbiome and Metabolomic Study (GEMM).

The changes included an increased abundance of pro-inflammatory microbial species and decreased abundance of protective and anti-inflammatory microbial species at various time before celiac disease, the study says.

The changes included an increased abundance of pro-inflammatory microbial species and decreased abundance of protective and anti-inflammatory microbial species at various time before celiac disease, the study says.

While no changes were seen in the type of microbes, metabolites and functional pathways, all of these were increasing or decreasing at the time of diagnosis in the children who went on to have celiac disease, Leonard said.

“The identified alterations point to a march from the preclinical stage of disease to a break of tolerance to gluten and the subsequent onset of celiac disease and may serve as microbial markers of progression towards disease onset,” the study authors wrote.

The gut microbiome of the first 10 infants who had developed celiac disease in the GEMM study were compared to the microbiomes of 10 who did not get celiac disease. The two groups were matched one-on-one in multiple ways, including sex, season of birth, the method by which they were delivered, and timing of the introduction of solid food and gluten.

About 500 children in the United States, Italy and Spain are being followed from birth to 10 years old in the GEMM study. Samples of blood and stool are collected, and parents fill out questionnaires about birth, feeding, and antibiotic exposure.

The comparison in this study was done with stool samples from both groups that had been collected at several points beginning 18 months before the 10 children developed celiac disease. 18 months is the youngest a child in the study has been diagnosed. Significant changes in the intestinal microbes, pathways and metabolites were found as early as 18 months before celiac disease developed, said Maureen Leonard, MD, lead study author and clinical director of the celiac center. “This was much earlier than we expected,” she noted.

Functional pathways represent the overall activity of the microbiome, including the metabolites being produced.

Researchers used metagenomic analysis to link microbial composition with function, highlighting changes in the pathways associated with increased or decreased inflammation. Metagenomics is the study of a collection of genetic material from a mixed community of organisms and usually refers to the study of microbial communities.

While some adenoviruses were detected, changes were limited so results of the study are only related to bacteria and archaea, single-celled organisms whose cells lack a defined nucleus.

Previous research has linked celiac disease and the reovirus in children. A higher frequency of enterovirus during early childhood was associated with later development of celiac disease in another study, but no association with adenovirus, which is also common in children. Another study has also explored the connection between the Epstein-Barr virus, which causes mono most often in teenagers and young adults, with celiac disease and other autoimmune conditions.

The longitudinal, GEMM birth-cohort study is giving investigators the evidence they need to move microbiome research from observations of associations to studies related to cause, Fasano said. Researchers are interested in whether changes in the microbiome are a cause or consequence of celiac disease. The study provided an opportunity to observe alterations in the earliest phase of celiac disease because scientists have specific data about the make-up of the microbiome of the children before celiac disease developed.

The study may also impact other autoimmune diseases. The investigation “establishes a roadmap” for long-term studies to better understand the role of the microbiome in the development other conditions and how to target treatments so they prevent autoimmunity, the authors wrote. The study notes there are other implications for autoimmune diseases, including the identification of microorganisms that might serve as biomarkers of future autoimmune disease.

GEMM is an ongoing research project. The first published study based on its evidence showed that cesarean delivery, antibiotics at birth and formula feeding cause changes in the gut of infants at-risk for celiac disease that are linked to dysfunction of the immune system and to inflammatory conditions. Early results of another GEMM study presented recently at Digestive Disease Week found that the breast milk of new mothers with celiac disease who are on the gluten-free diet is similar to the breast milk of new mothers who don’t have celiac disease.

“I think the most important thing about this study is that we identified alterations in the microbiome more than a year prior to celiac disease onset,” Leonard said. “This is very promising for potentially identifying ways to intervene before celiac disease develops.” Researchers expect about 50 children participating in the study to develop celiac disease before the investigation concludes. Additional data collected will be used to validate the findings of the current study and refine predictions that link specific microbiome shifts to the risk of developing celiac disease, according to the study. Future work will also analyze microbiome changes related to other influencing factors including timing of gluten introduction, amount of gluten consumes and exposure to viruses.

Study limitations noted by the authors include the small number of participants included in the analysis and potentially the collection and analysis of stool samples, which may not be the ideal measure of of small intestine microbiota, which is part of the gastrointestinal system of interest in celiac disease.

Opt-in to stay up-to-date on the latest news.

Yes, I want to advance research No, I'd prefer not to